Dewan learns Kafka - architecture principles and recent changes

Last week, I learned the basics of Kafka and continued my learning journey this week with Kafka’s architecture principles and issues around stability and scalability. I also learned about Kafka Improvement Proposals (KIP) - major changes in Kafka suggested by the community. In the second part of the Dewan learns Kafka blog series, I share these learnings and hope that you are learning with me.

What does it mean to design a high-performance system?

Kafka relies on some hardware, an operating system, the JVM, and the system it is connected to. Do you know what is Kafka capable of? If you had the best hardware, OS, and the correct mix of JVM and connected systems, what would be the maximum throughput and minimum latency from Kafka? This is without any optimizations on Kafka itself. Once you learn about the bar from your hardware, OS, and systems, then you optimize Kafka for your custom business needs.

Kafka was designed to have one cluster per organization and you would add as many brokers as you need. In the next section, you’ll see how Netflix views that principle but principles are more like guidelines and not set in stone. Kafka was designed to handle massive scaling of workload so more workload simply means adding more brokers. Kafka will self-rebalance once you remove brokers for reduced workload.

You can watch this keynote by Gwen Shapira to learn more.

How does Netflix use Kafka

When learning about designing fault-tolerant and scalable Kafka systems, I wanted to learn from use cases rather than simply reading the theory. I followed this talk to learn how Netflix uses Kafka for data pipelines and stream processing. The talk is from 2018 so some of the design and metrics will be different now.

In 2018, Netflix had 4000+ brokers and ~50 clusters in 3 AWS (2 US & 1 EU) regions to process 1T+ messages/day. For both data pipeline and stream processing, the data was non-transactional and the event order was not required for most of the topics. A typical Netflix Kafka cluster at that time had between 20 to 200 brokers - each with 4 to 8 cores, Gbps network, and 2 to 12 TB local disk. The brokers spanned across three availability zones within a region with rack aware assignment and Netflix used MirrorMaker (a stand-alone tool for copying data between two Kafka clusters) for cross-region replication for selected topics.

The rack awareness feature spreads replicas of the same partition across different racks. If you are able to define which rack each of your nodes belongs to, then Kafka is able to intelligently allocate replicas on nodes that do not share the same rack. This gives you better fault tolerance. If a rack goes down due to maintenance or power loss, you have a reduced chance that a leader and all of the replicas are located in that single rack. Obviously, this feature is only beneficial if you are able to spread your Kafka brokers across racks.

The availability of a Kafka cluster at Netflix is defined as the ratio of messages successfully produced to Kafka vs. total attempts. Their engineers understood that Kafka, as a stateful service, must provide fast failover to guarantee a high SLA (99.9999% availability at that time). Let’s talk about scalability now. Scaling regular workload and scaling internet-scale workload are not the same. In order to scale, you add brokers and add partitions to those brokers. There’s a limit on the number of partitions you can have in a Kafka cluster. It was 100,000 at the time of the talk and 2M+ when I’m writing this blog in 2022 (although it is suggested to keep the number of partitions around 200,000). There’s also an issue with partition reassignment because when you add new brokers and you reassign the ownership of the partition, the new broker has to copy the data of that partition from the leader. Not only is this a time-consuming process, but there’s also a significant increase in network traffic during that time.

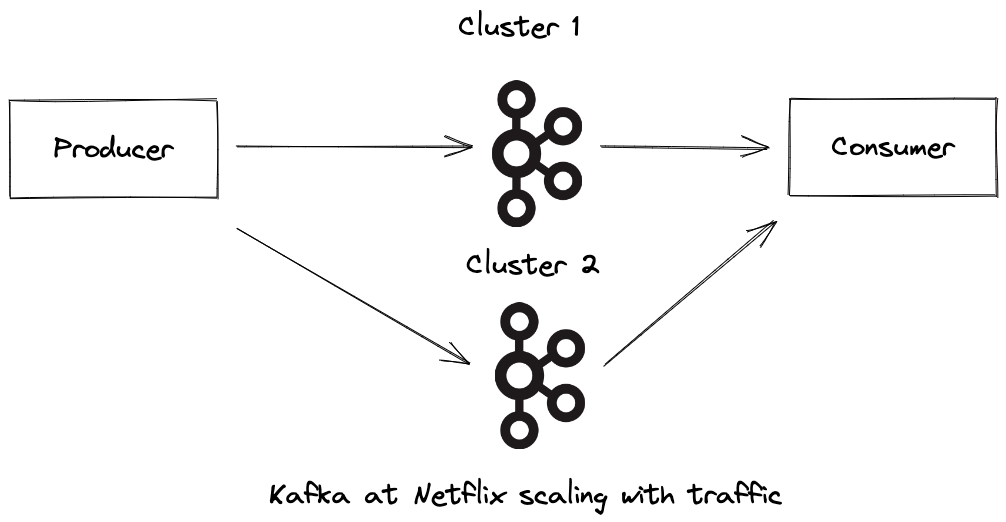

The benefit of cloud and managed services is that you can provision a Kafka cluster with the click of a button or an API call. Imagine you have a single cluster and producer/consumer. If you see a traffic increase, you add a second cluster add create topics in the second cluster. The next step is to have your producer write to both clusters and consumer read from both clusters. This is how you scale up. To scale down, you ask the producer to stop producing to the second cluster while the consumer is still reading from both clusters. Once all the data has been read or the data retention period has passed for the second cluster, you can have the consumer stop reading from the second cluster and safely remove the second cluster. The video shows advanced topics like topic failover and failover with traffic migration.

KIP-500 and KIP-405 - What and why

KIP-500 - Replace ZooKeeper with a Self-Managed Metadata Quorum

The community works together to continuously improve Kafka and KIP is a process for proposing a major change to Kafka. When learning about Kafka and its features, following the recent and ongoing KIPs is important as some features might get deprecated while others are being introduced. Two of the heavyweight KIPs I’ll mention are KIP-500: Replace ZooKeeper with a Self-Managed Metadata Quorum and KIP-405: Kafka Tiered Storage.

Last week, I stood up a Kafka cluster on a digitalocean VM. Before starting the Kafka broker service, the first thing I had to do is start the Zookeeper service:

bin/zookeeper-server-start.sh config/zookeeper.properties

Zookeeper keeps track of the metadata (the status of the Kafka cluster nodes, Kafka topics, partitions, etc) and it does so by writing to a shared log. While Kafka has so far worked great with Zookeeper, it is a separate system that makes learning, deploying, and managing Kafka difficult. KIP-500 talks about how Kafka can use itself to store the metadata. Kafka is pretty good at writing to shared log (that’s what it does primarily) and that’s why it makes total sense to move away from Zookeeper dependency. There is a number of benefits to this architectural decision:

- the metadata can be stored in memory rather than stored in Zookeeper resulting in a drastic reduction in recovery time from both controlled and uncontrolled shutdown

- doubling the maximum allowed number of partitions to 2M and the potential to reach 10M+ partitions per cluster

Colin McCabe goes deep in this video about KIP500 and the decision to get rid of Zookeeper.

KIP-405 - Kafka Tiered Storage

Kafka is an important part of data infrastructure and KIP-405 is based on a simple principle that recent data is much more valuable than old data. This means the latency to read recent data should be much low and you are willing to pay more for the storage. Historical data, on the other hand, is not read that often and can be stored away in some cheap/cold storage. Your data scientist might read that data once every few months. While throughput is still important for historical data, you should not care too much about the latency. The main benefit of this design decision is that it opens up elasticity. While you store most of the data in S3 or HDFS, you can store the amount of recent data in memory (which might only be a few MB). This means that rather than taking hours or days to copy all of the partitions and the data that no one would ever read; when you add a new broker, you only copy the recent data which is needed to serve the real-time traffic. An additional benefit to tiered storage is that if we can store data in cheap storage, we might not need to delete any data and keep an infinite history of data. Pluggable storage also means that you can swap the storage backend - whether it’s S3 or MySQL or store old Kafka data.

If you’d like to learn more, refer to the KIP itself or read Gustavo’s blog.

As I wrap up this week’s learning, I have some key takeaways:

- Great architectures have conceptual integrity. It doesn’t happen by accident and conscious decisions need to be made throughout the evolution of that software to keep the integrity.

- Picking the right abstraction opens up the inherent efficiencies of the underlying hardware. Trying to improve software without considering the hardware and OS optimizations is an uphill battle.

- Continuous improvement of software is directly proportional to the level of decoupling among its components.

While I explore topics to learn for next week, feel free to send suggestions my way. If you’re learning Kafka alongside, I’ll be super interested to hear your experience in the comments.