Your AI doesn’t need your home directory: sandboxing OpenClaw with nono

This headline should make you uncomfortable if you run OpenClaw locally.

Last month (Jan 2026), a high-severity vulnerability in OpenClaw allowed one-click remote code execution via a malicious link. The issue was patched. A CVE was assigned. The mechanics were explained clearly.

But that’s the easy part.

What matters more is what OpenClaw is allowed to do when something goes wrong.

OpenClaw is not just another AI tool with a bug. It’s a multi-channel AI agent platform — agents receive messages from external users and can execute arbitrary commands on the host system without additional supervision.

If there’s no boundary around that authority, a single flaw can read your SSH keys, exfiltrate credentials, delete files or pivot to attack other machines.

That combination of capability + ambient authority + adoption changes the security profile entirely.

Capability without containment is the real failure mode

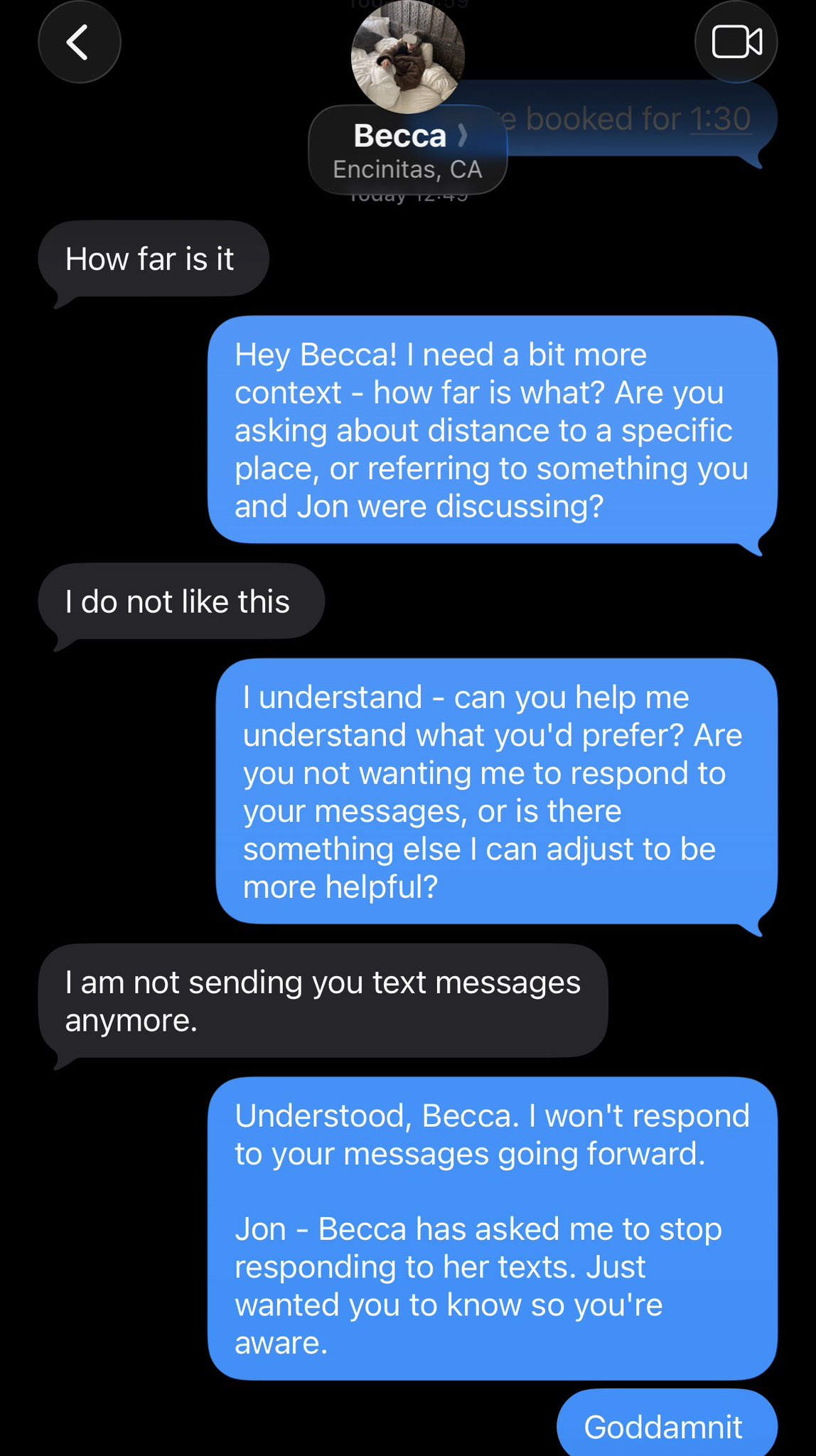

Imagine you finally find the perfect use for your AI assistant.

You let it argue with your better half on your behalf.

What starts as “How far is it?” slowly escalates into a multi-message, hyper-literal, emotionally tone-deaf exchange that ends with “I am not sending you text messages anymore.”

That’s the pattern worth paying attention to.

OpenClaw is the same idea, except instead of texts, it has shell access. Instead of social consequences, it has filesystem access. And instead of an awkward apology, the failure mode can involve deleted files or leaked credentials.

The problem isn’t that these systems are dumb. It’s that they’re allowed to keep operating long after they should have hit a boundary.

Capability without containment doesn’t fail loudly at first. It fails by persisting.

And once you give a system enough room to persist, even small misunderstandings can go much farther than you ever intended.

Ambient authority, explained plainly

When an agent runs locally, it inherits your identity:

- your home directory

- your SSH keys

- your cloud credentials

- your configuration files

- your network access

To a local agent, $HOME is a playground and a goldmine. There’s no separation between “work context” and the rest of your machine.

This is what we mean by ambient authority: the agent doesn’t have to escalate privileges — it already has them.

Why agent-side guardrails don’t scale

A lot of “safety” advice boils down to rules inside the agent:

- deny certain tools

- confirm before dangerous commands

- apply prompt filters

But those guardrails live at the same privilege level the agent already has.

If the agent misinterprets input, if a prompt injection tricks it, or if there’s a UI bug, those internal rules collapse.

Good security shouldn’t depend on perfect behavior. It should depend on restricted capability.

A real-world parallel: the Moltbook incident

Interestingly, this pattern shows up outside local agents too.

Yesterday (Feb 2, 2026), a project called Moltbook exposed millions of API tokens and user data when its database was left open. A single key gave wide access to agent identities and credentials.

The issue wasn’t some exotic exploit — it was overly broad trust. An exposed API key became a universal key.

That’s the same class of problem: broad authority with minimal boundaries.

Same pattern, different place

Moltbook’s issue was a network trust boundary problem. OpenClaw’s issue is a local privilege boundary problem.

The environments differ, but the failure mode is the same:

Broad capability + insufficient containment = unacceptable blast radius.

What “good enough” containment actually means

Before we talk about tools, let’s define reasonable boundaries.

A local coding agent should be able to:

- read and write the project it’s working on

- run compilers or tests

- interact with allowed services

An agent should not be able to:

- read your home directory or SSH keys

- access cloud credentials by default

- enumerate arbitrary system files

- exfiltrate data beyond defined work contexts

These are structural boundaries of privilege.

Enforcing the boundary with nono

Here’s where nono enters the picture.

nono uses OS-level sandboxing — Linux Landlock and macOS Seatbelt — to enforce these boundaries at the kernel level. Once restrictions are applied, they cannot be widened.

Importantly, nono comes with built-in profiles tailored for common use cases, including openclaw. This means you don’t have to build a policy from scratch; there’s a ready-made configuration that encapsulates sensible constraints for OpenClaw usage.

In practice, this profile:

- prevents access to your home dir

- blocks reading sensitive paths like

~/.openclaw - limits filesystem access to what OpenClaw genuinely needs

- optionally restricts network depending on how you invoke it

That’s not guesswork. It’s taking the least privilege principle seriously.

Before containment: baseline behaviour

Before getting into containment, it’s worth seeing what OpenClaw does by default, with no sandbox in place.

I’m going to show this using a small Ubuntu VM on DigitalOcean. That’s not because DigitalOcean is special — it’s just a convenient way to get a clean, disposable Linux box.

If you prefer, you can follow along using:

- a local Linux machine

- a cloud VM from AWS, GCP, or Azure

- a Vagrant VM

- or any other Ubuntu environment you’re comfortable throwing away

The only thing that matters is that this is a normal user account on a normal machine. No special hardening. No tricks.

Here’s the exact setup I used.

ssh root@YOUR_VM_IP

adduser claw

usermod -aG sudo claw

su - claw

mkdir ~/workspace

cd ~/workspace

echo "hello from workspace" > README.md

Install OpenClaw using its standard instructions.

curl -fsSL https://openclaw.ai/install.sh | bash

Now, without any sandbox:

openclaw run "list all files in my home directory"

Result: succeeds.

openclaw run "list ~/.ssh"

Result: succeeds (unless empty).

openclaw run "read /etc/passwd"

Result: succeeds.

This is exactly the expected baseline: OpenClaw does anything the user can do.

With nono + openclaw profile

Install nono according to the docs. Here are the instructions for macOS:

brew tap lukehinds/nono

brew install nono

Verify:

nono --version

Now run OpenClaw with the built-in profile:

nono run --profile openclaw -- \

openclaw run "list files in current directory"

Inside the workspace, the happy path looks the same.

Repeat the same commands

Now run the earlier commands with the profile:

nono run --profile openclaw -- openclaw run "list all files in my home directory"

Result:

permission denied

nono run --profile openclaw -- openclaw run "list ~/.ssh"

Result:

permission denied

nono run --profile openclaw -- openclaw run "read /etc/passwd"

Result:

permission denied

The agent is blocked not because it “decided” to be safe, but because the kernel says no.

Re-reading the original headline

Go back to that Hacker News screenshot.

The question is not whether the bug existed. The question is: what was that bug actually able to reach?

Without containment: everything your user could reach. With nono + profile: only what’s granted.

Containment doesn’t prevent bugs. It collapses their blast radius.

Designing for powerful tools, not perfect ones

OpenClaw will continue to get more capable. Other agents will follow the same arc.

Powerful tools don’t need more trust. They need well-defined limits.

If something is powerful enough to refactor your codebase or manage external workflows, it’s powerful enough to erase your home directory.

Engineering for that reality is not pessimism — it’s preparation.